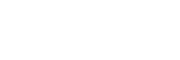

This week I reached the point in the new novel where I decided it was time to do an outline. That point is roughly 75 percent into the book.

My version of an “outline” is a one or two sentence summary of each chapter I’ve written so far. This helps me see the larger shape of the narrative and to catch any discrepancies in times and dates. (There are usually a lot of those since I have always had a somewhat fuzzy idea of what day of the week or even what month it is. I suppose that comes partly from living for so many years in Florida where one season is almost indistinguishable from another.) Outlining after-the-fact also lets me see the rising and falling tension and suspense. From this vantage point, I can sometimes see that I need to adjust the pace of the storyline or simply move chapters so that I avoid long passages of exposition and backstory–those necessary features that often can slow down the reading experience.

I’ve met a lot of novelists who outline extensively before they set out. Some writers even “write the last sentence before they write the first.” These are successful novelists, so obviously this system works for them. I’ve met one or two who write long outlines (200 or 300 pages) for novels that are only slightly longer than the outlines. These folks have also done quite well in the publishing world.

So I don’t think the way I work is necessarily better or worse than the way anyone else works. It’s simply the only way that I can manage to keep my excitement level high enough to forge through hundreds of manuscript pages and lots and lots of deletions.

I’ve always found Elmore Leonard’s take on this writer’s issue to be apt. “Why would I write the novel if I knew how it turned out?” That was his line. As usual, it’s succinct, dry and perfectly to the point.

I started my writing life as a poet and one of the aesthetic beliefs I acquired early and held to was that every poem should be a process of discovery. You start with something you know and work toward something you didn’t know when you began. Frost put it this way: “No tears for the writer, no tears for the reader.” He believed that the only authentic purpose for writing was to discover a new truth, or a new slant on the world.

So I start with only the most vague road map. I want to go to some general location–north or south. And I want to write about some general subject matter. So I always begin by doing a month or so of research on this subject matter. Sometimes that entails traveling to a place to learn about the people and location that I want to use. (As I did in Gone Wild when I traveled to Borneo and Brunei and Singapore to research the illegal trade in orangutans.) Sometimes it involves reading books and articles and other written info on the subject I’m tackling.

The obvious downside of writing without an outline is that sometimes I take a narrative path that looks good at the outset but turns into a dead end and must be deleted. I’ve sometimes had to delete a hundred pages because I took a wrong turn that I didn’t see till later.

I don’t recommend my method for other kinds of writing. Essays, for instance, require a little more planning and outlining.

I’m sure this college kid would’ve been a more successful student if he’d outlined.

My first two books I wrote without outlines … they took 7 years and 4 years respectively to finish. I then went in the opposite direction and have outlined half a dozen books to the nth degree, outlining each scene, practically each beat. I’m having difficulty with the current book, though, which is seeming to resist much in the way of planning, so I’m going to sneak up on it and start writing with an outline in my head and just one or two pointers in a plan. That should fool it.

Elmore Leonard is a hero of mine and I hate to argue with him, but I wasted years trying to find out where a given book was heading, and it seems much more efficient, in the end, to have at least some idea of the travel guide I’m using, even if I don’t have the precise road map …

Your last book, Mr Hall, certainly seemed to have been well-planned, as did the Thorn books, so whatever you’re doing you seem to have mastered the knack of reverse planning!

Yes to everything. I want to be surprised at how the story takes turns and resolves; and yes, that leads to some throwaways. Also, yes it leads to re-ordering. But that’s part of the fun, eh? Figuring out how to make it work because I know there’s something good in there, somewhere; so the challenge becomes saving/killing/rearranging to bring the pieces together into a cohesive, entertaining, well-paced tale with surprising twists and a satisfying (and hopefully unpredictable) ending. BTW – Carl Reiner famously started all of his novels with a single sentence that popped into his head. Then he wrote until the story ended (itself). Great piece on the old Tonight Show with him explaining his process to Carson. Carson says something like: “So, if I said, ‘Joe goes to the refrigerator to see what there is to eat and decides on a bologna sandwich.'” To which Reiner said: “Brilliant! I’m going to steal that!”

Your aptosch and mine are much alike. I love the Rlmore Leonard observstion.

I do outlines, scaffolds, chapter synopses, mind maps — and then my stories rebel and head off in directions entirely outside my jurisdiction. Sometimes it’s a good thing, sometimes it’s garbage. But the outline/scaffold/map gives me a level of security, which I so fondly crave.

Thanks for these insights. My outline for “The Constable’s Tale,” contained a quite a bit of detail in the early going, but got vaguer as it went along, which encouraged more of the discoveries you speak of. The most horrific story I know of involving someone who professes not to believe in outlines is Stephen King’s confession that he painted himself into such a corner in “The Stand,” with so many characters and subplots, that he was at a loss as to how to end it. After nearly having a nervous breakdown (by his own account), he settled on [PLOT-SPOILER] just blowing everybody up.